Manifesto of Libertarian Communism

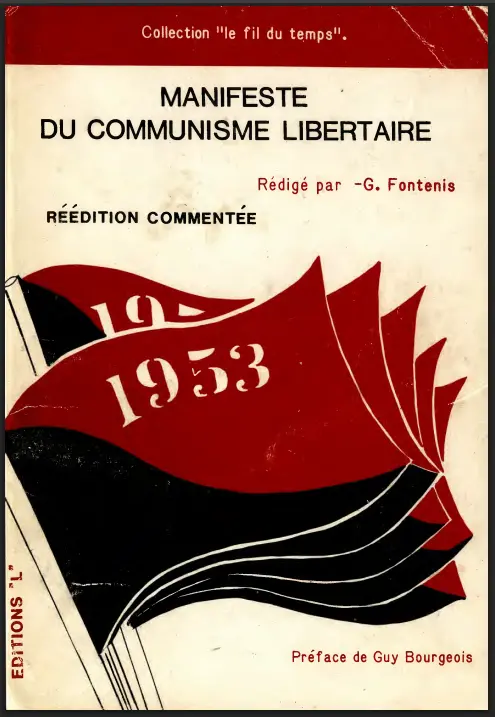

Text transcription of the book Manifesto of Libertarian Communism written by Georges Fontenis in 1953 and republished in 1985 by Éditions “L”, in the collection “Le Fil Du Temps”.

🔗Foreword

For the author of these lines, the Manifesto of Libertarian Communism is made up of faces, voices, comrades who have disappeared, who have been lost track of, who have abandoned the social struggle, others who still participate in it, and those who have followed other paths. It is also, for the young man I was, an older brother, Georges Fontenis.

We were coming out of the war, of the Nazi occupation, and we were fundamentally questioning bourgeois society and its mechanisms of thought. In our search, we needed action, fraternity, the virus of activism had often seized us since the clandestine battles of the Resistance, which had disappointed our adolescent hopes.

Our meeting place was a small shop on the Quai de Valmy, on the edge of the Saint-Martin canal, which had all the romantic decor one could want… It was the headquarters of Le Libertaire, which we unabashedly defined as the “only revolutionary newspaper.”

That era was the scene of an incredible ferment of ideas. Existentialism dominated the media, and the last survivors of the surrealism of the 1920s had finally encountered anarchy (“bearer of torches”). They published a “note” every week in Le Libertaire, and Georges Fontenis was mentioned in a poem by Breton.

Then came our ruptures, our conflicts, our different paths which we believed to be separate… Can I be impartial in writing the preface to this manifesto?

According to the foreword written by the editorial committee of the time:

“The capitalist system” had reached “its culminating point of crisis.”

Yet we had seen nothing yet!

The committee went on:

“All the patch-up recipes and solutions of the pseudo-State communism have failed…”

You can see that we were already posing the present-day problems correctly.

Thirty years ago, the Socialist Party was already in power and the Communist Party, in the midst of the “Cold War,” was in its darkest Stalinist period. The Algerian war had not yet shaken French society. May ‘68 had not happened.

No one was yet talking about self-management. Yet the Manifesto was already advocating “Direct workers’ power.”

We had found that anarchism constituted the only coherent solution.

According to our illusions, the Anarchist Federation was the revolutionary force. We joined it naturally.

The F.A. claimed to make anarcho-syndicalists, libertarian communists, and Stirnerian individualists coexist within it. This did not happen without all sorts of conflicts. But we listened to the Spanish libertarians idealize their Revolution. We were sure of ourselves. Facing the Stalinists, we had our own “model” of society. Regardless of the context, many among us saw the anarcho-syndicalist schema applied in France.

The only really easy-to-find anarchist writings, apart from the accounts concerning Spain (none of which were truly self-critical), were those of Sébastien Faure, apostle of the synthesis of libertarian tendencies. Very quickly, we saw that synthesis became compromise, and even conciliation, mediation—in other words, reformist thought. Worse, some anarchists assigned us a useful role within bourgeois democracy (cf. Bontemps).

When we debated with Marxists, we were seen as dreamers or naïve, when we didn’t have to defend some nonsense from Le Libertaire produced by the synthesist trend (cf. a campaign for Céline). Our words were perceived as the amusing stories told at dessert.

Finally, we found other texts by digging through libraries, by looting the collections of older activists, proving to us that the anti-authoritarian current was a serious elaboration: exactly as we intuited.

Let it be said that it was impossible to find in bookstores the slightest work by Bakunin, Guillaume, Malatesta, etc., while Marxist publications were flourishing.

It was the merit of the libertarian communist current to recover the foundational texts and to rediscover the class origin of social anarchism, which the Manifesto boldly asserted.

To our amazement, we also discovered that the materialist analysis as conceived by the Marxists was not at all seen as a divergence in the eyes of the libertarian current of the First International, and that the border between Marxism and anarchism was not always very clear.

We came to pose the problem of revolutionary organization, of its role, and we sought a lineage with Bakunin’s Alliance and the “Platform of Archinov.” Our research, our discoveries, our reflections appeared in a column of Le Libertaire entitled “Essential Problems” and in the journal “Anarchist Studies.” The Manifesto written by Georges Fontenis expresses most of it.

Faced with the “humanist” anarchists whom we called among ourselves the “wishy-washy,” there was a will to provoke. The Manifesto uses the vocabulary proscribed among Marxists: party, political line, discipline. The term “dictatorship of the proletariat” is used as a paragraph heading, even if its principle is then denied in the text. We did not hesitate to affirm that the other tendencies had only a vague link with anarchism, of which our current was the only representative. We would later come to realize the impossible challenge presented by this attempt to rehabilitate such an ambiguous term.

The other tendencies of the F.A. felt the aggressiveness of our approach. Quickly, it was asked whether we were not infiltrated agents of Bolshevism—it was whispered, it was said, and many years later, it was written.

On the other hand, the Manifesto denied Proudhon the quality of being an anarchist. Once the other tendencies were eliminated, the F.A. became the hard and pure organization: the Libertarian Communist Federation, while another F.A. was formed.

It is in this context that one must judge today the excesses of the Manifesto.

There was a much more important problem to solve than the conflicts with anarchist currents which interested only us: in the postwar workers’ movement, the Communist Party objectively, really represented the working class. The latter saw it as its Vanguard in the Leninist sense of the term. The importance given to this reality by certain intellectuals explains their ambiguous behavior and what, with hindsight, appears to us as their errors.

Above all, the Manifesto of the L.C. poses the problem of building another political vanguard. The Platform of Archinov defined a practice towards the masses entirely contrary to the Leninist principles of “leadership external to the class.” We tried as much as possible to refer to it.

In Archinov, one found the principle of the necessary ideological unity. Coming out of the confusionism of the F.A., the Manifesto takes it up forcefully.

From ideological unity also flows tactical unity. Here, there appeared an inability to find a specific solution: the definition of tactical unity is very close to Leninist practice, with discipline and splitting considered natural, which was the ailment of all sectarian groups since then.

The asserted federalism seems arbitrarily tacked on to the whole to preserve a libertarian packaging.

Thus, the F.C.L. risked becoming a little lookalike Communist Party. It failed before that, to the great joy of the “Humanists” of the F.A.

The approach of the Manifesto was important. It may have seemed adventurous, like any militant project that disturbs. It had weaknesses and errors that are easier to see in hindsight than in immediate action. I only show here how many of his companions felt the “line” of Georges Fontenis, from whom some, myself included, eventually parted ways.

Yet, the Manifesto of Libertarian Communism was necessary. For the first time within the postwar libertarian movement, it marked a clear break with the humanist tendencies of conciliation. Before its time, it defined the first anti-reformist self-management movement. After its publication, nothing was the same:

Beyond conflicts between individuals, black and red of the early days, the Union of Anarchist Communist Groups, T.A.C. and, before the U.T.C.L., the M.C.L. in 1969, then the O.C.L. of 1971, continued the deepening, the search for a new form of self-managed revolutionary organization, the way to insert the libertarian communist current.

Nothing would have existed without the necessary rupture of 1954 of which Georges Fontenis was the first architect.

Would the U.T.C.L. have existed?

I must finally say how much Georges Fontenis was pursued by the hatred of the supporters of anarchist orthodoxy. This hatred, which I also sometimes felt the effects of, has not died out. A recent article in a F.A. journal reminded us that some still cannot master their old resentments and have not reached the age of serenity.

This preface by an old comrade of Georges Fontenis, who often had conflicts with him and has not hidden them, also wants to be the expression of his deep and affectionate friendship.

For the rest: after thirty years, everything is still to be built.

Guy Bourgeois

🔗Introduction

At the moment when the capitalist system has reached its culminating point of crisis, at the moment when all the “patch-up” recipes and “solutions” of state pseudo-communism have failed and prove themselves incapable of bringing anything other than misery, slavery, war, it seemed necessary and urgent to pose, in a manifesto, the analysis and the libertarian communist solution.

On the other hand, for a long time militants, embarrassed in front of questions posed by sympathizers and newcomers, wished that one day this manifesto could be written, which would contain in a few pages the essentials of libertarian communism, with the necessary clarifications on key subjects such as the State and the Revolution.

In writing, at the request of the near-unanimity of militants, this booklet, on the basis of the essential ideas, of the principles recognized by libertarian communists, Georges Fontenis did not intend to create a new doctrine.

What we present today is therefore not a definitive form of the doctrine of authentic communism, which will always go on perfecting, clarifying, illuminating itself in the light of experiences, of historical facts.

The goal was only to give of this doctrine the clearest, most coherent, most “up-to-date” summary possible, which could be conceived today.

One will find there the essential thought of the first founders and the best theorists of anarchist communism: Bakunin, Kropotkin, Malatesta; one will find there sometimes almost word for word passages from the “Statutes of the Alliance” by Bakunin; one will find there what can be retained as fundamental in the ideas of the “Platform” of Makhno and his companions — sum of the reflections inspired by the conduct of anarchists during the Russian Revolution of 1917; one will find there the main points and the spirit of the Pact of Alliance and the Program which presided over the birth in 1920 of the Italian Anarchist Union; one will find there the theses defended today in Italy by the militants of the Groups of Anarchist Action of the Proletariat, faithful to the teachings of Bakunin and Malatesta; one will find there the spirit of the conceptions of the Spanish Anarchist Movement and of its experiences of 1936. One will find there finally the development of the principles which animate the anarchist-communist-revolutionary movement in France, as it has emerged from the complex struggles of tendency, especially since 1913, and as it is continued by the French movement of today, as attested by its principles, its statutes, and its orientation.

Fontenis did not see why one should be original at all costs: he took up fragments of articles from the cahiers “Études Anarchistes” or from “Le Libertaire” which had already attempted partial clarifications, for example on the problem of active minorities or revolutionary violence.

He especially wanted to make a modest work of gathering, to make this clarification which could serve as a solid theoretical basis for the militants of a revolutionary organization, a clarification whose absence has often been felt and which was so awaited.

Some will perhaps be alarmed by the lexicon used, but it was necessary not to hesitate to use the language of everyone, the language that the public immediately understands and that Bakunin, Kropotkin, Malatesta used without false shame; party, political line, discipline are words which, well specified, can only frighten those whose revolutionary vigor, courage in the face of situations and in the face of words, have been destroyed by a whole heap of literature and pseudo-anarchist sentimental palaver.

Fontenis retouched, corrected, clarified by taking into account the observations, approvals, criticisms that were brought to him by militants, by readers of Le Libertaire, in which these “Essential Problems” appeared in the last months of 1952. Some chapters have therefore undergone notable additions, others have been revised.

As it is, this little work — which represents rather long labors, numerous and delicate clarifications — will be a precious tool for all militants, the bedside book of all those who come to join us for the good fight.

The Editorial Committee

🔗Libertarian Communism, Social Doctrine

It is during the 19th century, with the development of capitalism and the first great workers’ struggles, and more precisely within the First International (from 1864 to 1871), that a social doctrine appears, called “revolutionary socialism” (in reaction against legalist, reformist, or statist socialism), or “antiauthoritarian socialism” or “collectivism,” then later “anarchism” or “anarchist communism” or “libertarian communism.”

This doctrine, this theory, appears as a reaction of organized socialist workers. It is, in any case, linked to the existence of a class antagonism which keeps growing. It is a historical product, it is born in certain conditions of history, of the development of class societies, and not from the idealist critique of certain thinkers.

The role of the founders of the doctrine, Bakunin mainly, was to express the true aspirations of the masses, their reactions and their experiences, and not to artificially create a theory based on an abstract, purely ideal analysis, or on previous theories. Bakunin, and with him James Guillaume, then Kropotkin, Reclus, J. Grave, Malatesta, etc., start from the observation of the condition and the forms of organization and struggle of workers’ associations and peasant masses.

The origin of class struggles of anarchism is incontestable.

How is it, then, that very often, anarchism has been considered as a philosophy, a morality or ethics independent of class struggle, thus as a humanism detached from historical and social conditions?

We see several reasons for this. On the one hand, the first anarchist theorists sometimes sought to refer to the opinions of writers, economists, historians who preceded them, especially Proudhon (whose many writings undeniably show anarchist conceptions).

The theorists who followed them have even sometimes found in writers like La Boétie, Spencer, Godwin, Stirner, etc., thoughts having an analogy with anarchism, in the sense that they showed an opposition to forms of exploitative societies and to the principles of domination they discovered in them. But the theories of Godwin, Stirner, Tucker, are only reflections on society without taking account of History and the forces which determine it, without taking account of the objective conditions which pose the problem of Revolution.

On the other hand, in all societies based on exploitation and domination, there have always existed gestures of revolt, individual or collective, sometimes with a communist and federalist or genuinely democratic content, so that people have sometimes come to consider anarchism as the expression of man’s eternal struggle for freedom and justice: a vague concept, insufficiently founded on the sociological or historical level, and tending to assimilate anarchism to a vague humanism, based on the abstract notions of “humanity,” of “freedom.” The bourgeois historians of the Workers’ Movement have always been keen to mix anarchist communism with individualist, idealist theories, and are for a large part responsible for the confusion. They are the ones who wanted to link Stirner to Bakunin.

It has sometimes happened, by forgetting the conditions of the birth of anarchism, to reduce it to a sort of super-liberalism, losing its materialist, historical, revolutionary character.

But in any case, if revolts prior to the 19th century and the reflections of certain thinkers on the relations between men and human categories have prepared anarchism, there was anarchism as a doctrine only starting from Bakunin.

Certainly, the revolts and writings to which reference is made in the past of humanity were themselves born, too, because there was exploitation of social categories by others. The works of Godwin, for example, clearly express the existence of class society, even if they do so in an idealist, confused way. And the alienation of man by the group, the family, religion, the State, morals, etc., is indeed of a social nature, it is indeed the expression of a society divided into castes or classes.

One can say that attitudes, reflections, ways of acting that we can call rebellious, non-conformist, anarchist in the vague sense of the term, have always existed.

But the coherent formulation of an anarchist communist theory dates from the end of the 19th century, and continues every day, becomes more precise, perfects itself with the contribution of historical experience.

Anarchism therefore cannot be assimilated to an abstract or individualist philosophy or ethic.

It was born in and through the social, and it was necessary to wait for a given historical period and a given state of class antagonism for anarchist communist aspirations to clearly manifest themselves, for the phenomenon of revolt to lead to a coherent and complete revolutionary conception.

Anarchism not being an abstract philosophy or ethic, it cannot address itself to the abstract man, to man in general. For anarchism, there is not, in our societies, man as such: there is the exploited man of the despoiled categories and there is the man of the privileged categories, of the ruling class. To address “man” is to fall into the error or sophism of the liberals addressing the “citizen” without taking account of the economic and social conditions of citizens. And to address man in general, neglecting the fact of the existence of classes and of class struggle, being satisfied with empty rhetorical declamations about Liberty, Justice, in general and with capital letters, is to allow all the apparently liberal — in fact conservative or reactionary — bourgeois philosophies to become embedded in anarchism, to pervert it into a vague humanitarianism, to emasculate the doctrine, the organization, and the militants. There was a time, indeed, and this is still seen in some countries in certain groups, when anarchist propaganda degenerated into the whinings of absolute pacifism or a kind of sentimental Christianity. It was necessary to react, and today anarchism sets out to attack the old world with something other than nebulous considerations.

It is to the despoiled, to the exploited, to the proletariats, to the working and peasant masses that anarchism, social doctrine and revolutionary method, addresses itself, because only the exploited class, as a social force, is a revolutionary factor.

Do we mean by this that the class of workers constitutes the messianic class, that the exploited possess a providential clairvoyance, all the qualities and no defects? That would be to fall into worker idolatry, into a new kind of metaphysics.

But the exploited class, alienated, mystified, frustrated, the proletariat, taken in its broad sense and including both the working class properly speaking (composed of manual workers and having a certain common psychology, a certain way of being and thinking), and other wage earners such as employees, or again, in other words, all those who have only executive functions in production and in the political order, thus who are far from management, this class can alone by its economic and social position overthrow power and exploitation. Only the producers can realize workers’ management and what would the revolution be if it were not the passage to management by all producers?

The proletarian class is therefore the revolutionary class par excellence, since the revolution it can accomplish is a social revolution and not only a political one and in emancipating itself, it emancipates all humanity: by breaking the powers of the privileged class it abolishes classes.

No doubt, in present society, classes do not have precise limits. It is in the course of various episodes of class struggle that separation occurs. There are no precise limits, but there are two poles: proletariat and bourgeoisie (capitalists, bureaucrats, etc.). The so-called middle classes are torn in times of crisis and orient themselves toward one or the other pole: they are incapable by themselves of providing a solution because they have neither the revolutionary characteristics of the proletariat nor really the management of present society like the bourgeoisie properly speaking. We observe for example in strikes that a part of technicians (especially those who are in fact specialists, those in design departments for example) rally to the working class, while another part, technicians who have a managerial role and a large part of the foremen, move away from the working class, at least for a while.

Syndical reality has always relied on experience, on pragmatism, unionizing certain layers and not others, according to their role, their function. In any case, it is function and state of mind that allow the characterization of a class, more than remuneration.

There is therefore the proletariat. There is its most determined, most active part, the working class properly speaking. There is also something broader than the proletariat and which includes other social layers that must be drawn into action: these are the popular masses which include in addition to the proletariat small peasants, poor artisans, etc.

It is not a question of falling into a mystique of the proletariat but of appreciating this precise fact that the proletariat, despite the slowness of its awakening, its setbacks and its defeats, is in the end the only real lever of the Revolution.

Here, we cannot omit to quote this fundamental text of Bakunin:

“To understand that, since the proletarian, the manual laborer, the man of toil, is the historical representative of the last slavery on earth, his emancipation is the emancipation of everyone, his triumph is the final triumph of humanity…”

No doubt, it happens that men belonging to privileged social categories, breaking with their class, with the ideology and advantages of their class, come to anarchism. Their contribution is considerable, but in a way, these men become proletarians.

For Bakunin, again, the “revolutionary socialists,” that is, the anarchists, address themselves “to the working masses of both the cities and the countryside, including all men of good will from the upper classes who, breaking with all their past, would frankly join them and fully accept their program.”

But one cannot therefore say that anarchism addresses man in general, the abstract man, without taking into account his milieu.

To take away from anarchism its class character would be to condemn it to formlessness, to condemn it to empty itself of its content, to become an inconsistent philosophical pastime, a curiosity for the intelligent bourgeois, an object of sympathy for the man of heart in search of an ideal, a subject of academic discussion. We therefore conclude:

Anarchism is not a philosophy of the individual or of man in general.

Anarchism is, if you will, a philosophy or an ethic but in a very particular, very concrete sense, it is so by the aspirations it represents, by the aims it sets itself and which Bakunin’s quote recalls: “His (the proletarian’s) triumph is the final triumph of humanity…”

Proletarian, of class, as to its origin, it is only in its aims that it is generally human or, if you will, humanist.

It is a socialist school, and even, to be more precise: the only true socialism or communism, the only valid theory and method to achieve a society without castes and without classes, realizing liberty and equality.

Social anarchism or anarchist communism, or again libertarian communism, is a revolutionary social doctrine, addressing itself to this proletariat whose aspirations it represents, whose, if you will, it expresses the true ideology, the ideology of which this proletariat tends to become conscious through its experiences.

🔗The Problem of the Program

Anarchism being a social doctrine, it manifests itself through a set of analyses and proposals setting out the goals and tasks, that is to say, through a program. And it is this program that constitutes the common platform for all members of the anarchist organization, a platform outside of which the gathering could only be based on vague, confused sentimental aspirations, without there being any real unity of views.

A question then arises: can the program not be a synthesis taking into account what is common between people claiming the same ideal, or more precisely, the same label or a neighboring label? That would then be to seek a factitious unity where, in order to avoid oppositions, one would keep most of the time only what is unimportant: one would find a common platform but almost empty.

The experiment has been tried too many times and from “syntheses”, unions, cartels, alliances, and agreements, nothing ever emerged but inefficiency and very quickly a return to conflicts: reality posing problems to which each brought divergent or opposing solutions, clashes reappeared and the vanity, the uselessness of the pseudo common program which could only be a refusal to act, were demonstrated.

On the other hand, the very idea of bringing out a program from scratch, by looking for small common points, assumes that all proposed points of view are correct, that a program thus can spring from brains, in the abstract.

Yet, a revolutionary program, the anarchist program, cannot be a program created by men to then be imposed on the masses. The opposite must occur: the program of the revolutionary vanguard, of the active minority, must only be the expression, condensed and vigorous, clear and made conscious and evident, of the aspirations of the exploited masses called upon to make the Revolution. In other words: the class before the “Party.”

What must determine the program is therefore the study, the experience, even the tradition of what is permanent in the aspirations of the masses. There thus reigns in the elaboration of the Program a certain “empiricism”, avoiding dogmatism, avoiding the substitution of a schema elaborated by a small revolutionary group for what is indicated by the action and consciousness of the masses. In its turn, the elaborated program, brought to the knowledge of these masses, can only develop their consciousness. Finally, the program thus defined can be modified as the analysis of the situation and of the tendencies of the masses advances, can be formulated in more just and clearer terms.

So conceived, the program is no longer the set of secondary points that unite (or rather do not separate) people who may believe themselves close, but it is a set of analyses and proposals to which only those rally who approve it and commit to spreading it and realizing it.

But one will say, it is necessary that this platform be elaborated, written, by someone or by a team. Certainly, but, since it is not just any program, but the program of social anarchism, only the proposals considered as concordant with the interests, the aspirations, the consciousness, and the revolutionary capacity of the exploited class will be accepted. Then, one can truly speak of synthesis since it is no longer a question of eliminating important things that separate, since it is a matter of merging into a common and new text proposals that could fuse on the essential. It is the role of study meetings, assemblies, congresses of revolutionaries to recognize a program, to gather together and to found their organization on this program.

The tragedy is that several organizations claim to authentically represent the working class, as much the reformist socialist or authoritarian communist organizations as the anarchist organization. Only experience can decide, can ultimately give reason to one or the other.

There is no possible revolution without the revolutionary masses grouping together on a certain ideological unity, without them acting in the same direction. That means that for us, through their experiences, the masses will eventually find the path of libertarian communism. That also means that the anarchist doctrine is never finished as regards its detailed, applicational views, and that it is made, completed, at every moment according to historical experiences.

It seems that partial experiences like the Paris Commune, the popular Russian revolution of 1917, the Makhnovshchina, the achievements of Spain, the strikes, the fact that the working class is making a hard trial of total or partial State socialism (from the USSR to nationalizations and the betrayals of political parties in the West), it seems that all this allows us to affirm that the anarchist program, with all the modifications of which it is susceptible, represents the direction in which the ideological unity of the masses will be revealed.

For today, let us be content to summarize this program as follows: the society without classes and without State.

🔗Relations between the Masses and the Revolutionary Vanguard

We have seen, concerning the problem of the program, what our general conception is of the relationship between the oppressed class and the revolutionary organization defined by a program (that is to say, the party in the pure sense of the term). But we cannot be content to say: “the class before the party.” We must develop, explain how the active minority, the revolutionary vanguard, is necessary without thereby becoming a general staff, a dictatorship over the masses. In other words, we must show that the anarchist conception of the active minority has nothing aristocratic, oligarchic, or hierarchical about it.

🔗I. Necessity of the Vanguard

There exists a conception for which the spontaneous initiative of the masses is sufficient for any revolutionary possibility.

It is true that history shows us a certain number of facts that we can consider as spontaneous mass movements, and these facts are precious because they show the capacities and resources of the masses. But this in no way leads to accepting a general, fatalistic conception of spontaneity. Such a myth leads to a populist demagogy, to the praise of a rebellism without principles, possibly reactionary, to passivity and capitulation.

On the opposite side, we find a purely voluntarist conception giving revolutionary initiative to the vanguard organization alone. Such a conception leads to a pessimistic evaluation of the role of the masses, to an aristocratic contempt for their political capacity, to an abstract conduct of revolutionary action and consequently to its defeat. This conception contains in germ the bureaucratic and statist counter-revolution.

Close to the spontaneous conception, we observe a theory according to which mass organizations, trade unions for example, are not only self-sufficient, but sufficient for everything. This conception, which claims to be absolutely anti-political, is in fact an economist conception. It has often been expressed in the form of “pure syndicalism.” But we point out that if the theory is to hold, its supporters must refrain from formulating any program, any objective, under pain of forming, however little, an ideological organization, or of constituting a general staff advocating a given orientation. Therefore, this theory is coherent only if it limits itself to a socially neutral conception of social problems, to empiricism.

Equally distant from spontaneism, empiricism, and voluntarism, we base the necessity of the specific revolutionary anarchist organization conceived as the conscious and active vanguard of the popular masses.

🔗II. Nature of the Role of the Revolutionary Vanguard

Unquestionably, the revolutionary vanguard plays a guiding, leading role in relation to the mass movement. The polemics seem vain to us on this subject, for what other purpose could a revolutionary organization have? Its very existence attests to this leading, guiding character. The real question is how this role is conceived, what meaning we give to the word “leading.”

The revolutionary organization tends to create itself by the very fact that the most conscious workers feel its necessity in the face of the uneven development, the insufficient cohesion of the masses. What must be specified is that the revolutionary organization must not constitute a Power over the masses; its guiding role must be conceived as consisting in formulating, expressing an ideological, organizational and tactical orientation, a precise, elaborated, adapted orientation, based on the aspirations and experiences of the masses. Thus, the directives of the organization are not external imperatives but the considered expression of the general popular aspirations. The guiding function of the revolutionary organization, in the absence of any coercive possibility, can only be manifested by striving to make its ideology triumph, by obtaining that the popular layers deeply absorb its theoretical principles and tactical directives.

It is a struggle by ideas and by example. And if one does not forget that the program of the revolutionary organization, the path and means it indicates, are the reflection of the aspirations and experience of the masses, that the organized vanguard is basically the mirror of the exploited class, one understands that “direction” is not “dictatorship,” but a coordinated orientation, that it is opposed on the contrary to bureaucratic manipulations of the masses, to militarism, to herd mentality, that it must set itself the task of developing the direct political responsibility of the masses, that it aims to develop the capacity for self-organization of the masses. This conception of “direction” is therefore both natural and educational. Likewise, better-prepared, more trained militants, within the organization, play towards the other militants a role of guide, educator, so that all may become solidly informed militants, always alert both in theory and practice, so that all may in turn become organizers.

The organized minority is the vanguard of a more numerous army, drawing its reason for being from the existence of this army: the masses. If the active minority, the vanguard, detaches itself from the mass, it can no longer exercise its function, it becomes a clique or a class.

The revolutionary minority can be, in the last analysis, only the servant of the oppressed. It has enormous responsibilities but no privilege.

Another aspect of the nature of the revolutionary minority is its permanence: there are periods when the minority embodies and expresses a majority which tends to recognize itself in the active minority, but there are periods of retreat during which the revolutionary minority is no more than an islet in the storm. It must then maintain itself in order to be able to quickly regain the audience of the masses as soon as circumstances become favorable again. Even isolated and cut off from its popular bases, it acts according to the constants of popular aspirations, maintaining its program against all odds. It may even be led to certain isolated acts intended to awaken the masses (attacks, insurrections). The difficulty is then to avoid cutting itself off from reality, turning into a sect, an authoritarian general staff, drying up by living off schemas, or trying to act without being understood, pushed or followed by the popular masses. To avoid this degeneration, it must keep in touch with events, with the environment of the exploited, be attentive to the slightest reactions, the slightest revolts or achievements, study minutely the society of the moment, its contradictions, its weaknesses, its possibilities of evolution. Thus, the minority, by participating in all forms of resistance and action (which can go, according to the conditions, from demands to sabotage, from silent resistance to revolt), keeps the possibility of orienting and developing the slightest movements. By striving to maintain or acquire a general, panoramic vision of social facts and their evolution, by adapting its tactics to the conditions of the moment, by being present, the minority remains faithful to its mission, avoids dragging behind events, becoming a simple apparatus external and foreign to the proletariat, and being overtaken by it. It avoids taking purely abstract calculations and schemas for the true aspirations of the proletariat. It maintains its program but by revising it and correcting its errors according to the facts.

Whatever the circumstances, the minority must never forget that its supreme goal is to disappear by identifying itself with the masses when they reach the highest degree of consciousness, in the course of the revolutionary realization.

🔗III. In What Forms Can This Role of the Revolutionary Vanguard Be Exercised?

Practically, the influence of the revolutionary organization can be exercised in the masses in two ways: there is work in constituted mass organizations and the work of direct propaganda. This second type of activity is exercised through the press, agitation and demands campaigns, cultural debates, gestures of solidarity, commemorative demonstrations, conferences, meetings, and this direct work, which can sometimes be accomplished during activities organized by others, is indispensable to assert oneself and to reach certain sectors of public opinion, otherwise inaccessible. It is of primary importance in the workplace as well as in the place of residence. But this work does not pose the problem of how “direction” can avoid being “dictatorship.”

It is otherwise for activity within constituted mass organizations. First, what can these organizations be?

These organizations are generally of an economic nature, founded on the social solidarity of their members, but their functions can be multiple: defense (resistance, mutual aid), education (training in self-government), offensive (tactical demands, expropriation on the strategic level), management. These organizations, unions, workers’ struggle committees or others, even when they assume only one of these possible functions, present a direct interest for work in the masses.

And alongside economic organizations, there exists a multitude of popular organizations through which the specific organization can establish contact with the masses. These are, for example, cultural, leisure, aid organizations, in which the specific organization can find energies, suggestions and experiences, can extend its influence by bringing its orientation, by fighting there against the aims of hegemony and control of the State and politicians, for the defense of the proper character of these organizations by making them centers of self-government and revolutionary mobilization, germs of the new society (elements of the society of tomorrow already existing in today’s society).

In all these mass organizations, economic and social, influence must be exercised and strengthened not by a system of external decisions but by the active and coordinated presence of revolutionary anarchist militants in these organizations and in the positions of responsibility to which they are normally called according to their abilities and attitude. It must be specified, however, that the militant must not allow himself to be confined to purely administrative, absorbing functions which would leave him neither the time nor the opportunity to exercise real influence. Political adversaries indeed often try to “imprison” revolutionary militants in this way.

This work of “infiltration,” as some would say, must tend to transform the specific organization, from a minority into a majority — at least from the point of view of influence.

It must also tend to avoid any monopolism which would end up having all the tasks — even those of the specific organization — absorbed by the mass organization, or on the contrary to assign to only the members of the specific organization, exclusively, the leadership of the mass organizations, excluding all other opinions. On this subject, it must be specified that the specific organization must promote and defend in the mass organizations not only a democratic and federalist structure and functioning, but also an “open” structure, that is to say, which facilitates the access of these organizations to all still unorganized elements, so that these organizations acquire new social forces, extend their representative character and are better able to give the specific organization maximum contact with the mass.

🔗Internal Principles of the Revolutionary Organization or Party

What we have said about the program, the role and the forms of activity of the vanguard clearly means that this vanguard must be organized. How?

🔗I. Ideological Unity

It is understood that to act, a coherent set of ideas is needed. Contradictions, hesitations prevent any penetration. On the other hand, the “synthesis” or rather the agglomeration of disparate ideas, having only points in common without real importance, can only produce confusion and cannot prevent that very quickly the divergences, which are essential, prevail.

Apart from the reasons we have found in the analysis of the problem of the program, apart from the deep ideological reasons concerning the nature of this program, there are thus practical reasons which dictate ideological unity as the basis of a true organization.

The expression of this common and unique ideology can be the fruit of a synthesis but only in the sense of the search for a unique expression of deeply related ideas, whose essentials are common.

Ideological unity is constituted by the program as we have previously considered it, and as we will define it further on, libertarian communist program expressing the general aspirations of the exploited masses.

Let us clarify further that the specific organization is not the gathering, the agreement of a contractual form between individuals bringing particular and artificial ideological convictions. It is born and develops in an organic, natural way, because it corresponds to a real need and on a certain number of programmatic data, not created from scratch, but reflecting, let us repeat, the deep aspirations of the exploited. The organization therefore has a class base, although it admits elements coming from privileged classes and in a way rejected by them.

🔗II. Unity of Tactics, Collective Method of Action

On the basis of the program, the organization determines a common tactical orientation. This is what makes it possible to draw all the advantages of the organization: continuity and constancy in work, compensation of the weaknesses of some by the abilities and strengths of others, concentration of efforts, economy of forces, possibility of responding at any moment to needs, to opportunities, with maximum effectiveness. Unity of tactics avoids dispersion, rids the movement of the harmful effect of several tactics opposing each other.

It is on this subject that the problem of the determination of tactics arises. As far as ideology, the fundamental program, the principles if you like, there is no problem: they are recognized by the unanimity of the organization. If there is divergence on the essentials, there is a split. And the newcomer into the organization accepts these basic principles, which can only be modified by unanimous agreement or at the cost of a separation.

It is quite different for questions of tactics. Unanimity can be sought, but only up to the point where, to be achieved, it would amount to putting everyone in agreement by deciding nothing: the black-white agreements leave of an organization only an empty shell, without substance (and without usefulness since the purpose of the organization is precisely to coordinate forces towards the same goal). It must therefore be admitted that when all the arguments have been given for the different proposals present, when discussion can no longer be usefully prolonged, when similar and fundamentally identical opinions have merged, and there remains an irreducible opposition between the proposed tactics, the organization must find a way out. And there are only four possible:

a) Decide nothing, thus refuse to act, and then the organization loses all reason to exist.

b) Accept different tactics, let everyone remain on their positions. The organization can allow this in certain limited cases, on points not of capital importance.

c) Consult the organization by a vote which allows a majority to emerge, the minority having agreed to sacrifice its point of view in public action, reserving the right to continue to develop it within the organization, considering that if it responds more to reality than the majority point of view, it will eventually triumph in the test of facts.

It has sometimes been argued the lack of objectivity of this process, number not necessarily meaning truth, but it is the only possible one. It does not manifest any coercive tendency since it is applicable only because the members of the organization accept it as a rule, and the minority accepts it as a necessity, allowing the experience of the accepted tactical proposals to be made.

d) When all agreement proves impossible between majority and minority on a crucial point that requires a position to be taken by the organization, then the split occurs, naturally, inevitably.

In all cases, it is a unity of tactics that seeks to be realized, and besides, except for this pursuit, congresses would only be confrontations without results and without practical utility. That is why the first possible outcome (a), that is, deciding nothing, is to be rejected in all cases, and the second (b), that is, the admission of several tactics, can only be quite exceptional.

Of course, it is only the bodies where the whole organization is represented which can deliberate on the tactical line to be established (conferences, congresses, etc.).

🔗III. Collective Action and Discipline

Once this general tactic (or orientation) is decided, the problem of its application arises. It goes without saying that if the organization has defined for itself a line of collective action, it is so that the militant activities of every member or every group of the organization are in accordance with this line. In the case where a majority and a minority have emerged but both parties have agreed to continue working together, no one can feel aggrieved since everyone has beforehand subscribed to this form of activity and participated in developing the line. This freely accepted discipline has nothing in common with militarism and passive obedience to orders. There is no coercive apparatus to impose a point of view not accepted by the whole organization: there is simply respect for commitments freely made as much for the minority as for the majority.

Of course, militants and the different levels of the organization can take initiatives but only insofar as they do not contradict the agreements made and the measures taken by the regular bodies, that is to say, if these initiatives are in fact applications of collective decisions but in the details of activities, when they engage the whole organization, each member must consult the organization through its representative and liaison bodies. Thus, collective activity and not activity personally decided by separate militants.

Thus, each member participates in the activity of the whole organization as the organization is responsible for the revolutionary and political activity of each of its members, since they do not act on the political level without consulting the organization.

🔗IV. Federalism or Internal Democracy

Far from centralism which is the blind submission of the masses to a center, federalism allows at once the necessary centralizations and the free determination of each member and their control over the whole. It engages the participants only on what is common to them.

Federalism, when it brings together groups based on material interest, rests on a pact and the basis of unity can sometimes be weak. This is the case in certain sectors of trade union action. But in the revolutionary anarchist organization, it is a matter of a program representing the general aspirations of the masses, the basis of gathering (the principles, the program) is more important than the differentiations and unity is very strong: rather than a pact or contract, one should speak of functional, organic, natural unity.

Federalism must therefore not be understood as the right to manifest one’s personal whims without regard for the obligations contracted towards the organization.

It means the agreement concluded between members and groups with a view to common work, towards a common goal, but a free agreement, a considered adhesion.

Such an agreement implies on the one hand that the participants fulfill in the most complete way the duties accepted and conform to the decisions taken in common; it implies on the other hand that the organs of coordination and execution are designated and controlled by the whole organization in its assemblies and congresses, their obligations and responsibilities being precisely defined.

It is therefore on the following bases that an effective anarchist organization can exist:

– Ideological unity – Unity of tactics – Collective action and discipline – Federalism

🔗The Libertarian Communist Program

🔗I. The Aspects of Bourgeois Domination: Capitalism and the State

It is necessary, before indicating the goals and solutions of libertarian communism, to examine, in broad outline, the adversary we are facing.

We observe that as soon as human societies have been divided into categories (in particular due to the division of social labor), there have been antagonisms between social classes and, since the oldest demands and revolts, a chain of struggles led for a better life and a more just society.

In what we are permitted to know of the history of humanity, we note that societies are not united, but crossed by two very different camps, both in relation to their situation and from the point of view of their social functions: the proletariat (in the broad sense of the word) and the bourgeoisie.

This situation is accompanied by a fact: the class struggle, whose character can vary, sometimes complex, imperceptible, sometimes open, rapid, clearly observable.

This struggle is very often masked by oppositions of secondary interests, conflicts between groups of the same class, complex historical facts and, at least in appearance, with no direct relation to the existence of classes and their antagonism, but fundamentally, this struggle is always directed towards the transformation of existing society into a society that would meet the needs, the necessities and the conception of justice of the oppressed, and thereby, into a classless society, liberating all humanity.

The structure of any society always expresses in its law, its morality, its culture, the respective situation of social categories of which some are exploited, enslaved, and others are holders of property and authority.

In modern society, economy, politics, law, morality, culture, are based on the existence of privileges, monopolies of one class and the violence organized by this class to maintain its supremacy.

🔗Capitalism

Very often, the capitalist system is considered as the only form of exploitative societies. Yet, capitalism is a relatively recent economic and social form and human societies have known many other forms of subjugation and exploitation, from clans, barbarian empires, ancient cities, feudalism, Renaissance cities, etc.

The analysis of the birth, development, evolution of capitalism was the work of all the socialist theorists of the beginning of the 19th century (Marx and Engels only having systematized them), but this analysis does not properly account for the general phenomenon of the oppression of one class by another and its origin.

It is pointless to engage in the verbal discussion of whether authority preceded property or vice versa. The current state of sociology does not permit an absolute decision, but it appears evident that economic, political, religious, moral, etc. powers have been intimately linked from the beginning. In any case, one cannot limit the role of political power to only the role of an instrument of economic powers. Thus, the analysis of the capitalist phenomenon has not been accompanied by a sufficient analysis of the “State” phenomenon, because the focus was on a very limited portion of history and only anarchist theorists, especially Bakunin and Kropotkin, have sought to give full importance to this phenomenon that too often was limited to the state of the period of the rise of capitalism.

Today, the evolution of capitalism, passing from classical capitalism to monopoly capitalism then to directed capitalism and state capitalism, generates new social forms which summary analyses of the State can no longer account for.

What is capitalism?

a) It is a society of antagonistic classes where the exploiting class holds and controls the means of production.

b) In capitalist society, all goods, including the labor power of the wage-earner, are commodities.

c) The supreme law of capitalism, the motive for the production of goods, is not the needs of men, but the increase of profit, that is, the surplus produced by workers, beyond what is strictly necessary for them to live. This surplus is also called surplus value.

d) The increase in labor productivity is not followed by the valorization of capital which is limited (underconsumption). This contradiction, which is expressed by the “tendential fall of the rate of profit,” creates periodic crises, which lead the holders of capital to all sorts of procedures: restriction of production, destruction of products, unemployment, wars, etc.

Capitalism has known an evolution:

-

Pre-capitalist period: As early as the end of the Middle Ages, the feudal economy sees the development within it of the merchant and banking bourgeoisie.

-

Classical or liberal or private capitalism: with individualism of capital holders, competition, and expansion (after the primitive accumulation of capital, through dispossession, plunder, the ruin of peasant populations, etc… the capitalism that was established in Western Europe has the world to conquer, formidable sources of wealth and markets that seem immense). The bourgeois revolutions, by eliminating feudal obstacles, help the development of the new system.

It is industrialization, technical progress that were at the origin of the existence of the capitalist form of production, and of the passage from the merchant bourgeoisie of the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries to the industrial capitalist bourgeoisie. They continue to develop.

During this period, crises are few, not very serious, the State plays a background role because competition eliminates the weak, it is the free play of the system. It is the period of steam, coal, on the technical level, of private property, of the individual boss, of competition and free trade on the economic level, of parliamentarism on the political level, of total exploitation and the most frightful misery of wage-earners on the social level.

- Monopoly capitalism, agreements, or imperialism: productivity increases, but markets shrink or do not increase in the same proportion. Fall in the rate of profit of over-accumulated capital.

Agreements (trusts, cartels, etc.) replace competition, joint-stock companies replace the individual boss, protectionism intervenes, the export of capital is added to that of goods, financial credit plays a major role, the merging of banking capital and industrial capital forms financial capital which domesticates the State and calls for its intervention.

It is the period of oil, electricity, on the technical level; agreements, protectionism, overaccumulation of capital and the tendency towards a fall in the rate of profit, crises, on the economic level; wars, imperialism, development of the State on the political level. War is a necessity to overcome crises, destruction frees up markets. On the social level: workers’ misery, but social laws limit certain aspects of exploitation.

- State capitalism: everything that characterizes the previous period is accentuated. Wars are no longer enough to overcome crises. A permanent war economy is required which invests enormous amounts of capital in war industries, without adding anything to the crowded market of goods; appreciable profit is provided by State orders.

This period is characterized by the takeover by the State of the most important economic sectors, of the labor market.

The State becomes capitalism, customer, supplier and supervisor of works and labor, and, consequently, increasingly ensures control of orientation, of culture, etc.

Bureaucracy develops, discipline and regulation are imposed in work and justify increasingly strict planning.

Exploitation and wage labor are maintained like the other essential characteristics of capitalism, but under the appearance of socializing forms (statutes, social security, pensions, etc…) which mark the ever greater subjugation of the proletarian.

The forms of state capitalism are varied: German national-socialism, Stalinist national-socialism, increasingly extended dirigisme of the “democracies” but presenting a mitigated form (due to a still extensive surplus value-market reserve of the colonies). Politically as economically, this period tends to take a totalitarian form.

Statism manifests itself therefore in forms at once political, economic, cultural: State financing, war economy, major works, labor service, concentration camps, population transfers, ideologies justifying the order of totalitarian things (varied ideologies: a counterfeit of the Marxist-Leninist ideology in the USSR, race for Hitler’s National Socialism, ancient Rome for Mussolini’s fascism, etc.).

🔗The State

Capitalism, despite its transformations or adaptations, retains permanent characteristics: surplus value, crises, competitions, etc. The State can no longer be considered only as the public organization of repression in the hands of the ruling class, the agent of the bourgeoisie, the policeman of capitalism.

An examination of previous forms of State before the rising period of capitalism, and of present forms of State, leads us to consider that the State has another value than that of an instrument.

The medieval State, the State of the absolute monarchies of Europe, the pharaonic State, etc. have been realities by themselves, so to speak, they have realized the State-dominant class.

And the State of the imperialist period of capitalism, the present State, tends, from superstructure, to become itself structure.

For the ideologists of the bourgeoisie, the State is the regulating organ of modern society. This is true, but it is so on the basis of an order that is the subjugation of the majority to a minority. It is therefore the organized violence of the bourgeoisie against the workers, it is the apparatus of the ruling class. But alongside this instrumental character, it tends to acquire a functional character, itself becoming the organized ruling class. It tends to overcome the antinomies between the leading groups in politics and in economics, it tends to fuse into a single block the forces which hold economic power and political power, the different sectors of the bourgeoisie, either to increase its repressive weight internally, or to increase its expansive pressure externally. It moves towards the unity of the political and the economic, extending its hegemony over all activities, integrating workers’ unions, etc., transforming the wage-earner properly speaking into a modern serf completely subjugated but with a minimum of guarantees (indemnities, social security, etc…). It is no longer an instrument, but a power in itself.

At this stage, in the process of being realized in all countries, even in the USA, attempted by Nazism and almost perfectly achieved in the USSR, one may even wonder whether it is still appropriate to speak of “capitalism” or whether this degree of development of the imperialist stage of capitalism should not be considered as a new form of exploitative society which is already something other than capitalism. The difference would then no longer be quantitative, but qualitative: it would no longer be a degree of evolution of capitalism but something else, really new and different. But this question is above all a question of appreciation, of terminology, which may seem premature and of no real relevance at present.

It is enough for us to express thus the form of exploitation and subjugation towards which bourgeois society tends: the State as a class apparatus, and as the very organization of the class, at once instrumental and functional, superstructure and structure, tends to unify the powers, all the forms of domination of the bourgeoisie over the proletariat.

🔗II. The Characteristics of Libertarian Communism

We have tried to summarize as clearly as possible the aspects of bourgeois society that the Revolution aims to liquidate by giving birth to a new society: the anarchist communist society. Before examining how the revolutionary fact can be envisaged, it is necessary to specify the essential characteristics of libertarian communist society.

🔗Communism: from the lower phase to the higher phase or perfect communism

One will never do better to define communist society than to repeat the old formula: “From each according to his means, to each according to his needs.” First, it affirms the total subordination of the economy to the needs of human development in the abundance of goods, the reduction of social labor and the reduction of each person’s share in this labor to his strength, to his real abilities. The formula thus expresses the possibility of the total development of man.

Next, this formula presupposes the disappearance of classes, the collective possession and exploitation of the means of production because only this exploitation by the community can allow distribution according to needs.

But the perfect communism of the formula “to each according to his needs” presupposes not only collective property (managed by workers’ councils, or “syndicates” or “communes”), but also an advanced development of production, that is, abundance. Now, it is certain that when the revolutionary fact occurs, the conditions do not allow this higher stage of communism, and the situation of scarcity means the persistence of the economic over the human, therefore a certain limitation and then the application of communism is no longer that of the principle “to each according to his needs,” but only the equality of income or the equality of conditions, which amounts to egalitarian rationing or else to distribution through monetary tokens of limited validity and having only the role of distributing products which are neither rare enough to be strictly rationed, nor abundant enough to be “taken at will”: this monetary system allowing the consumer to decide himself how to spend his income. It has even been considered to stick to the formula “to each according to his work,” taking into account the backwardness in the psychology of certain categories attached to the notions of hierarchy: considering the necessity of proceeding by differentiated wage rates or by giving advantages such as the reduction of working time to maintain and develop production in certain “inferior” or unattractive activities, or to obtain the maximum productive effort or else to obtain workforce mobility. But the importance of these differentiations would be minimal and communist society, even in its lower phase (which some call “socialism”) tends towards as great an equalization as possible, an equivalence of conditions.

🔗Libertarian Communism

A society where collective property and the egalitarian principle are realized cannot be a society where economic exploitation persists, where there is a new regime of classes. It is precisely the negation of it.

And this is true even for the lower phase of communism which, if it manifests a certain constraint of the economy, in no way justifies the persistence of exploitation. Otherwise, the revolution, almost always starting from a situation of scarcity, would be automatically canceled. The libertarian communist revolution does not realize, at the start, a perfect or highly developed society, but it destroys the bases of exploitation, of domination. It is in this sense that Voline spoke of an “immediate but progressive Revolution.”

But there is another problem: that of the State, that of the type of political, economic, and social organization. Certainly, the Marxist and Leninist schools themselves see the disappearance of the State in the higher phase of communism, but consider the State as a necessity during its lower phase.

This so-called “workers’” or “proletarian” State is considered as organized constraint, made necessary by the insufficiency of economic development, the lack of development of human capacities, and—at least for a first period—the struggle against the remnants of the former ruling classes defeated by the Revolution or more precisely the defense of the revolutionary territory inside and out.

What can be, in our view, the form of economic management of communist society?

Unquestionably workers’ management, management by all producers. Now, we have seen that, increasingly, exploitative society has achieved the unification of power, that the conditions of exploitation are less and less private property, the market, competition, etc… and that thus, economic exploitation, political coercion, and ideological mystification are fused, the essential basis of power and the dividing line between exploiters and exploited classes being the management of production.

Under these conditions, the essence of the revolutionary act, the abolition of exploitation, is realized through workers’ management and this management represents the system of replacement of all powers. It is all the producers who manage, who organize, who realize self-administration, self-government, true democracy, liberty in economic equality, the suppression of privileges and of directing and exploiting minorities, who take into account economic necessities, the necessities of the defense of the Revolution. The administration of things replaces the government of men.

The abolition of the opposition between leaders and executants in the economy, if it were accompanied in politics by the maintenance of this opposition in the form of the dictatorship of a party or a minority, would have no future or would create a conflict between producers and political bureaucrats. Workers’ management must therefore realize the suppression of all power of a minority, therefore of any State. It can no longer be a matter of domination, of hegemony, of a class, but of management and administration, as much on the political as on the economic level by the economic mass organizations, the communes, the people in arms. It is a direct power of the people, it is not a State. And if this is what some call the dictatorship of the Proletariat, the term is equivocal (we will return to it), but it has nothing to do anymore with the dictatorship of the Party or a bureaucracy. It is simply true revolutionary democracy.

🔗Libertarian Communism and Humanism

Thus anarchist communism or libertarian communism, by realizing the society of the full flourishing of man, of human man, of total man if one may say so, opens an era of permanent progress, of gradual transformation, of transitions.

It thus creates a humanism of aim, whose ideology was born within class society, in the very course of the development of class struggle, a humanism which has nothing in common with the mystifications about abstract man such as bourgeois liberals try to show us within their class society.

And thus, the Revolution based on the powerful lever of the masses, of the proletariat, by emancipating the exploited class, emancipates all humanity.

Thus the initial negation of a worthless humanism leads us to the struggle for a libertarian communist society whose very progress and aim are nothing else, in the last analysis, than the development of man.

🔗The Libertarian Communist Program

🔗I. The aspects of bourgeois domination: capitalism and the State

It is necessary, before indicating the aims and solutions of libertarian communism, to examine, in broad outline, what adversary we are faced with.

We observe that as soon as human societies have been divided into categories (in particular due to the division of social labor), there have been antagonisms between social classes and, since the most distant demands and revolts, as a chain of struggles led for a better life and a more just society.

In what we are permitted to know of the history of humanity, we note that societies are not united, but crossed by two very different camps, both in relation to their situation and from the point of view of their social functions: the proletariat (in the broad sense of the word) and the bourgeoisie.

This situation is accompanied by a fact: the class struggle, whose character can vary, sometimes complex, imperceptible, sometimes open, rapid, clearly observable.

This struggle is very often masked by oppositions of secondary interests, conflicts between groups of the same class, complex historical facts and, at least in appearance, without direct relation to the existence of classes and their antagonism, but fundamentally, this struggle is always directed towards the transformation of current society, into a society that would answer to the needs, the necessities and the conception of justice of the oppressed, and by that very fact, into a classless society, liberating the whole of humanity.

The structure of any society always expresses in its law, its morality, its culture, the respective situation of social categories of which some are exploited, enslaved, and others holders of property and authority.

In modern society, economy, politics, law, morality, culture, rest on the existence of privileges, of monopolies of a class and of the violence organized by this class to maintain its supremacy.

🔗Capitalism

Very often, the capitalist system is considered as the only form of exploitative societies. Yet, capitalism is a relatively recent economic and social form and human societies have known many other forms of subjugation and exploitation, from clans, barbarian empires, ancient cities, feudalism, Renaissance cities, etc.

The analysis of the birth, the development, the evolution of capitalism was the work of all the socialist theorists of the beginning of the 19th century (Marx and Engels having only systematized them), but this analysis does not properly account for the general phenomenon of the oppression of one class by another and its origin.

It is pointless to engage in this verbal discussion of whether authority preceded property or vice versa. The current state of sociology does not allow for an absolute answer, but it seems obvious that economic, political, religious, moral, etc. powers have been intimately linked from the start. In any case, one cannot limit the role of political power to only the role of instrument of economic powers. Thus, the analysis of the capitalist phenomenon has not been accompanied by a sufficient analysis of the “State” phenomenon, because the focus was on a very limited portion of history and only anarchist theorists, especially Bakunin and Kropotkin, have tried to give all its importance to this phenomenon which too often was limited to the state of the period of the rise of capitalism.

Today, the evolution of capitalism, passing from classical capitalism to monopoly capitalism then to directed capitalism and state capitalism, gives rise to new social forms which summary analyses of the State can no longer account for.

What is capitalism?

a) It is a society of antagonistic classes where the exploiting class holds and controls the means of production.

b) In capitalist society, all goods, and including the labor power of the wage earner, are commodities.

c) The supreme law of capitalism, the motive for the production of goods, is not the needs of men, but the increase of profit, that is to say, the surplus produced by the workers, over and above what is strictly necessary for them to live. This surplus is also called surplus value.

d) The increase in the productivity of labor is not followed by the valorization of capital which is limited (under-consumption). This contradiction, which is expressed by the “tendential fall of the rate of profit” creates periodic crises, which lead the holders of capital to all sorts of procedures: restriction of production, destruction of products, unemployment, wars, etc.

Capitalism has known an evolution:

-

Pre-capitalist period: From the end of the Middle Ages, the feudal economy sees the bourgeoisie of merchants and bankers developing within it.

-

Classical or liberal or private capitalism: with individualism of capital holders, competition, and expansion (after the primitive accumulation of capital, by dispossession, pillage, the ruin of peasant populations, etc… the capitalism that was established in Western Europe has the world to conquer, formidable sources of wealth and markets that seem immense). The bourgeois revolutions, by removing feudal obstacles, help the development of the new system.

It is industrialization, technical progress which were at the origin of the existence of the capitalist form of production, and of the passage from the merchant bourgeoisie of the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries to the industrial capitalist bourgeoisie. They continue to develop.

During this period, crises are few, not very serious, the State plays a background role because competition eliminates the weak, it is the free play of the system. It is the period of steam, coal, on the technical level, of private property, of the individual owner, of competition and free trade on the economic level, of parliamentarism on the political level, of total exploitation and the most frightful misery of wage-earners on the social level.

- Monopoly capitalism, of agreements, or imperialism: productivity increases, but markets shrink or do not increase in the same proportion. Fall of the rate of profit of over-accumulated capital.

Agreements (trusts, cartels, etc.) replace competition, corporations replace the individual owner, protectionism intervenes, the export of capital adds to that of goods, financial credit plays a major role, the fusion of banking capital and industrial capital forms financial capital which domesticates the State and calls for its intervention.

It is the period of oil, electricity, on the technical level; of agreements, protectionism, over-accumulation of capital and the tendency to fall in the rate of profit, of crises, on the economic level; of wars, imperialism, the development of the State on the political level. War is a necessity to overcome crises, destructions clear the markets. On the social level: working-class misery, but social laws limit certain aspects of exploitation.

- State capitalism: all that characterizes the previous period is accentuated. Wars are no longer enough to overcome crises. A permanent war economy is required which invests enormous capital in the war industries, without adding anything to the already crowded market of goods; appreciable profit is provided by State orders.

This period is characterized by the takeover of the State over the most important economic sectors, over the labor market.

The State becomes capitalism, client, supplier and supervisor of works and labor, and, consequently, increasingly ensures control of orientation, of culture, etc.

Bureaucratism develops, discipline and regulation are imposed in work and justify ever stricter planning.

Exploitation and wage labor are maintained as the other essential features of capitalism, but under the appearance of socializing forms (statutes, social security, pensions, etc…) which mark the ever-increasing subjugation of the proletarian.

The forms of state capitalism are varied: German national socialism, Stalinist national socialism, more and more widespread dirigisme of the “democracies” but presenting a softened form (due to a still large surplus value-market reserve of the colonies). Politically as economically, this period tends to take a totalitarian form.

Statism thus manifests itself by forms at once political, economic, cultural: State financing, war economy, major works, labor service, concentration camps, population transfers, ideologies justifying the order of totalitarian things (varied ideologies: a counterfeit of the Marxist-Leninist ideology in the USSR, the race for Hitler’s National Socialism, ancient Rome for Mussolini’s fascism, etc.).

🔗The State

Capitalism, despite its transformations or adaptations, keeps permanent features: surplus value, crises, competition, etc. The State can no longer be considered only as the public organization of repression in the hands of the ruling class, the agent of the bourgeoisie, the policeman of capitalism.

An examination of the forms of State prior to the rising period of capitalism, and of present forms of State, leads us to consider that the State has another value than that of an instrument.